Starting with the maps that make up the first (and only) volume of the Atlas Lingüístico de la Península Ibérica to be published, the atlas has been criticized for an excessively phonetic focus, but the truth is that the questionnaires and manner in which the fieldwork materials were collected show a great sensitivity towards material culture. In 1975, the ALPI’s director explained:

Para la sección de léxico resultó de gran ayuda el Atlas italo-suizo de Jaberg y Jud, cuyos volúmenes empezaron a aparecer por esa fecha.

Adoptamos su organización por temas etnográficos siguiendo el orden de fenómenos atmosféricos, accidentes geográficos, flora, fauna, cuerpo humano, familia, hogar, labores agrícolas, oficios artesanos, herramientas, animales domésticos, etc. Sobre esta base, el ALPI hubiera podido llamarse Atlas lingüístico y etnográfico, como de hecho lo es, aunque no pareciera indispensable indicarlo en el título.

[For the lexicon section, Jaberg and Jud’s Italian-Swiss Atlas, which began appearing volume by volume in those years, was a great help.

We adopted its organization by ethnographic topics, following the order of atmospheric phenomena, geographic features, flora, fauna, the human body, family, home, agricultural work, craft trades, tools, domestic animals, etc. Upon that basis, the ALPI could have been called a “Linguistic and Ethnographic Atlas”, as it is in fact, but it did not seem necessary to mention it in the title.]

(Navarro Tomás 1975: 12-13)

And this same defense of the linguistic and ethnographic nature of the ALPI is already present in the Introduction, where we read:

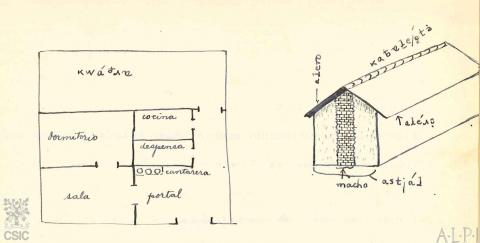

En el cuestionario de lexicografía no sólo se inquirían los nombres, sino también la forma y el uso de los objetos, y asimismo algunos refranes, costumbres y tradiciones, es decir, las encuestas tenían carácter lingüístico-etnográfico. [...] Se hicieron numerosas fotografías que permitían la confección de dibujos representativos de las variadas formas de los aperos, herramientas y utensilios tradicionales, muchos de los cuales han desaparecido ya en este último cuarto de siglo.

[In the lexicographic questionnaire we did not only ask for the names, but also the shapes and the uses of objects, as well as sayings, customs and traditions, that is, the surveys were linguistic-ethnographic in nature [….]. We took a number of photographs which allowed us to prepare representative drawings of the different types of implements, tools and traditional utensils, many of which have already disappeared in this last quarter-century.]

In reality, the ALPI questionnaires preserve rich ethnographic materials – plans, diagrams, drawings, sayings, short narrations, and in some cases photos – related to strictly linguistic content and fulfilling the function of completing the image and relationship between words and things which concerned the fieldworkers in their surveys. These materials can be consulted in the Gallery.

Questionnaire 760. Azuébar [Castellón/Castelló]

As has been noted, it was planned to systematically photograph certain items, of which this is an example. At the end of Notebook IIE and Notebook IIG, a note reminded the fieldworkers that they were to collect photographs of:

1.- The cart

A cart. Busmente (Asturias) FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

2.- The yoke

Yoke. Alquézar (Huesca). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

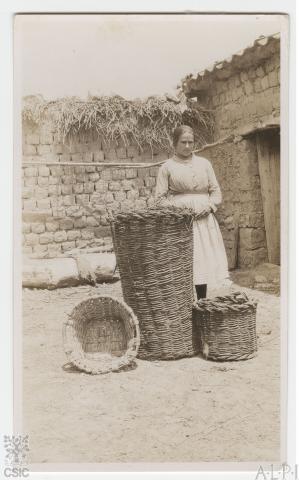

3.- Baskets made of wicker, straw, esparto grass, etc.

Alcubilla del Marqués (Soria). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

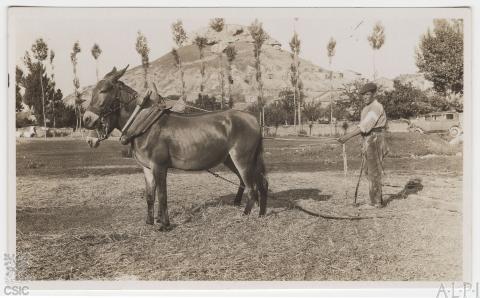

4.- Tilling implements (hoe, mattock, rake, cultivator, etc.)

A harrow drawn by a work-horse. Massalavés [Valencia]. FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

5.- The plough

Honrubia (Cuenca). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

6.- Harvesting implements (scythe, winnowing rake, flail, winnowing fork, sieve, etc.)

Threshing in Alcubilla del Marqués (Soria). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

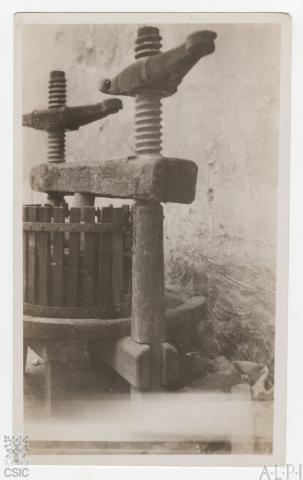

7.- Grapevines and wine (carrying cases, presses, etc.)

Wine press. Caudete (Valencia). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

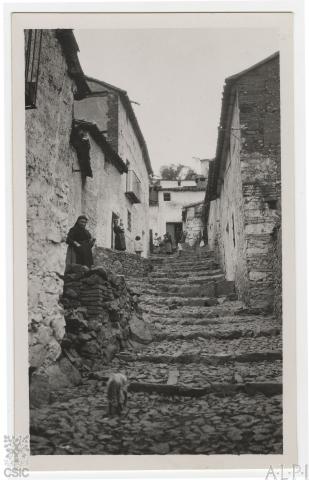

8.- Farmer’s house (grouping and outbuildings). Characteristic view of the village.

Drawing of the house. Valdepiélagos (Madrid) FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

A street in Fuencaliente (Ciudad Real). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

9.- Furniture (seats, chests, cradles, lamps, etc.)

Winder. Carrascosa del Campo (Cuenca). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

10.- Kitchen and kitchen utensils (dishes for cooking, eating, washing; receptacles for water, for washing clothes, etc.)

Biar (Valencia). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

11.- Articles of clothing (clothes, hats and footware)

Alcolea de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). People of different ages with a plow. FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

12.- People

A family in Camarenilla (Toledo). FRCFRC (Fondo Rodríguez-Castellano)

The Galería tab allows us to see many photos which are of ethnographic value collected during the ALPI surveys and preserved by Lorenzo Rodríguez-Castellano.

![760-II. Azuébar [Castellón/Castelló] 760-II. Azuébar [Castellón/Castelló]](http://alpi.cchs.csic.es/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/imagenes/760-II_Pagina_31.jpg)

![Draga arrastrada por una caballería. Massalavés [Valencia] Draga arrastrada por una caballería. Massalavés [Valencia]](/sites/default/files/imagenes/M_LRC046_0510r.jpg)